Adapting to the consequences of climate change

|

By Jeffrey Sachs

Until recently manmade climate change was believed to be a crisis of the distant future. We’ve learned, painfully, that we are already in the middle of manmade climate change, with worse to come. Rich and poor countries alike have been hard hit already: killer heat waves in Europe, extreme droughts in the United States and Australia, major floods and tropical cyclones in Asia and the Gulf of Mexico, extreme floods and droughts in Africa.

Part of our response, of course, must be to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases causing these changes. Another part, however, should be to adapt skillfully to the changes under way already.

”Adaptation science”

Climate change adaptation has become a new key concept of our time. Indeed, a new “adaptation science” is taking shape, which studies how societies in different parts of the world can best anticipate, prepare for and respond to climate shocks caused by manmade climate change and by simple bad luck. The starting point is that climate change poses many kinds of serious risks to society, with different risks for different regions. A sound response will require cooperation across many sectors and approaches.

Climate change was once simply described as “global warming”, but we appreciate now that the changes ahead go far beyond temperature alone. Climate changes affect crop productivity through changes in temperature, rainfall, river flows and pest abundance. Droughts and floods are becoming more frequent.

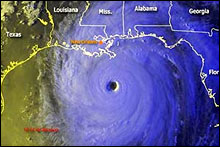

Tropical diseases, such as malaria, are being transmitted further afield. Extreme weather events, such as high-intensity hurricanes in the Caribbean and typhoons in the Pacific, are becoming more likely. Changes in river flow already threaten hydroelectric power, biodiversity and large-scale irrigation. Rising sea levels in the coming decades might inundate coastal communities and drastically worsen storm surges.

No region, not even the richest, is ready for these changes. All parts of the world will have to increase their scientific understanding, public awareness and investments to reduce climate risks and adjust to climate shocks as they occur. Yet the poorest, as usual, are most in the line of fire.

The tropics, home to a large proportion of the world’s poor, stand to bear the greatest adverse hits to agricultural productivity. The impoverished dry-land regions -- especially in Africa, the Middle East and Asia -- are already fighting the multiple disasters of drought, degraded pasturelands and rapidly rising populations. These dry-lands are now likely to become drier still, adding further potentially explosive pressures in places such as Darfur, Sudan, the Horn of Africa, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Skilful adjustment

Yet there are many things that the new adaptation science can allow us to do to adjust more skillfully to the coming shocks. New sustainable engineering techniques can teach poor farmers innovative ways to harvest and store rainwater to protect them from the rising risks of drought. Improved seed varieties can add drought-resistant traits to vital food crops. Improved weather and climate forecasting can give a region the advanced warning of seasonal and multi-year climate trends. Financial innovations can create novel market instruments, such as rainfall-linked bonds that enable regions to insure against climate risks.

There is talk about a new global fund to help poor countries to stop deforestation and thereby to help them to build up greater ecological resilience, as well as to protect biodiversity and reduce the emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Many of these changes are being put into place already. The International Research Institute of Climate and Society (IRI), part of Columbia University’s Earth Institute in the US, is working in many parts of the developing world to hone the new tools of adaptation science.

The millennium villages, led by the United Nations Development Programme and the Earth Institute, are empowering poor farmers to diversify crops, improve small-scale water management, insure against droughts and build a financial buffer against climate shocks. Countless other successes, on a small scale, are being demonstrated.

Global Humanitarian Forum

It’s now time to move the adaptation challenge, and the emerging adaptation science, to a much larger scale. The new Global Humanitarian Forum in Geneva will put both the challenges and the opportunities on the world stage. In less than two months time, when the world’s governments convene in Bali, Indonesia, to negotiate a new climate protocol to follow the Kyoto Protocol (which expires in 2012), adaptation should be high on the policy agenda.

We are moving into a new era, when we must not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions sharply, but learn to live wisely with the changes we have wrought.

Jeffrey Sachs is the director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University and a special adviser to United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

Source: M&G Online