International spotlight falls on SA’s rich biodiversity

|

From Thursday 15 to Saturday 17 May the Kruger to Canyons Biosphere Reserve was a hive of activity as national and international politicians, scientists, members of the public, educators and learners convened in this scenically spectacular area of the Lowveld to highlight our planet’s magnificent ecosystem and species diversity as part of International Biodiversity Day.

Originally initiated by GEO magazine (the European equivalent of National Geographic) in 2001, International Biodiversity Day (IBD) has become a prominent annual event on the international biodiversity calendar. The main objective of the initiative, which is funded by the German government, is to raise awareness of the vast natural diversity that exists on our planet and the need to protect it. The event also coincides with the United Nation's Convention on Biological Diversity ceremonies.

IBD is held in a different country each year, and this year South Africa, a country particularly richly endowed with a variety of ecosystems, fauna and flora, was selected as the pivotal IBD location. South Africa’s rich biodiversity was highlighted as international media converged on the area to broadcast the activities across the globe.

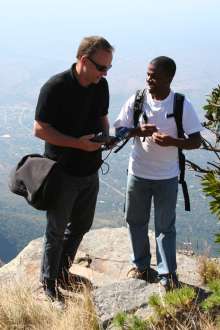

Scientists and members of the public (with the focus on learners) were involved in intensive biodiversity surveys in the Kruger to Canyons Biosphere Reserve over a period of 24 hours. The surveys were conducted at 18 sites along a transect from the top of the Blyde River in the Blyde River Nature Reserve (soon to be a national park), down to the Olifants River in the Kruger National Park, one of South Africa’s premier natural heritage sites.

As the theme for 2008 was “Biodiversity and Agriculture”, sites were identified in both conservation areas (as a reference) and agricultural areas. The objective was to explore what agriculture can contribute in terms of sustainable development (i.e. agriculture done in a way that has minimal effect on biodiversity) and the emphasis was on “ecosystem diversity” rather than “species diversity”.

Activities involved looking at the range of habitats represented, major groups of species present, and an estimate of ecosystem services provided at the sites.

The event was attended by the deputy minister of the Environment, Ms Rejoice Mabudafhasi, representatives of GEO Magazine, as well as German media and scientists.

On the Saturday afternoon, all participants met in Hoedspruit for the formal feedback session, a 300-drum group drumming event and a formal dinner. A report of all the data collected, as well as a documentary film of the proceedings was sent to Germany for the 9th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity that was held in Bonn, Germany from 19 – 30 May.

Mitzi du Plessis, a participant in the Kruger Park survey, recounts her experience:

Of mice and men ...

On the afternoon of Friday 16 May, after a morning spent exploring the dizzying heights of Mariepskop with the German delegation to IBD, I joined the Kruger Park night monitoring team at the Phalaborwa entrance gate. Armed to the teeth with binoculars, Sherman traps, bait, pen and paper we set off into the bush. All animals, birds and insects we encountered on the way were diligently recorded.

At a spot next to the Olifants River, Andrew Deacon of Kruger Park’s Scientific Services showed us how to concoct bait out of peanut butter, honey and oats for the Sherman traps. Each of us had a taste of the mixture – for scientific purposes of course – and it was declared to be “quite tasty”.

The traps were carefully hidden in various locations in the bush, which were marked for easy detection the following day. Satisfied with our progress, we concluded our survey with sundowners and snacks next to the river, lazily observed by a number of hippo from under heavy eyelids. A fish eagle swooped low over the water to perch on a tree on the opposite bank, uttering one long drawn out plaintive cry before it settled down for the night.

It was time for the team to follow suit and we tackled the return journey to Phalaborwa gate. In the beam of the vehicle’s lights we saw several rabbits, springhares, antelope and night birds. Near the Sable Dam we passed the ghostly figure of an elephant, so close that I could almost touch it.

After a quick indaba at the gate, we retired for the night, exhausted by the day’s exciting but rather strenuous activities.

A new day dawns

At dawn the next day, I encounter an interesting group of people at the Phalaborwa gate – the core team of the previous evening, two birders from the area (formidable, judging from their assortment of birding paraphernalia), the chairman of the greater Phalaborwa region’s herpetological society, environmental scientists, rangers, educators and learners from nearby schools … geared for action, determined to beat the other monitoring teams by recording the greatest number of species.

Our team leader, Dr Tony Swemmer of the SAEON Ndlovu Node, allocates responsibilities. The group is divided into two teams – a terrestrial team and an aquatic team. The terrestrial team will be exploring a transect of the mopane veld, and the aquatic team the riverine thicket along the Olifants River.

We venture into the bush in two separate vehicles. Anything that moves is recorded in a flash.

On reaching the monitoring location next to the Olifants River, we immediately investigate the result of our actions the previous evening. But the Kruger Park’s rodents had been far too clever – they either avoided the traps or helped themselves to the bait without getting caught.

Only one of the traps yields a furry creature – swiftly identified as a bushveld gerbil. Cameras flash. The unsuspecting gerbil has attained celebrity status overnight!

Then it is time to monitor the fish populations in the Olifants River. Kruger Park’s fish experts Andrew Deacon and Jacques Venter don their waterproof gear, get their electric apparatus in order and slowly enter the river. The process entails that the fish in the area between Andrew and Jacques are slightly immobilized by a weak electric current and float on the water, just long enough to be identified.

This is followed by another two monitoring processes. In the first of these, Andrew casts a net wide across the river to capture fishes in the deeper waters. The fishes are carefully removed from the net and placed in a bucket for later identification. While Andrew is engaged in this process, Jacques is skimming the shallow waters of the river for invertebrates. I venture closer to examine a dragonfly nymph, a rather clumsy and unattractive creature nowhere nearly resembling the graceful dragonfly.

Then the moment of truth dawns – identifying and recording the species. The yield is a rich harvest of fishes, insects and invertebrates. Carefully they are removed from the container, identified and returned to the water. The two learners in the group capture the proceedings on their cellphones.

Our lists of species are growing!

We split up into the designated teams. The fish and bird experts join the aquatic team. Our terrestrial team boasts the herpetologist Ken Watson and botanist, SAEON’s Dr Tony Swemmer. My task is to capture plant, insect and animal on film for later identification at the SAEON offices.

The location selected for our survey is a glade with tall trees and a stony outcrop for reptiles. The team members line up and start walking slowly in the same direction through the bush, about five metres apart, recording all the species we encounter. On the flanks, armed with a hand-held GPS unit, are elephant expert Yolanda Pretorius and game guard Elvis Shabangu, expertly handling both his rifle and the GPS unit. To assist us in the identification, Dr Tony Swemmer alternates between the members. All very scientifically correct.

Herpetologist Ken Watson is the only team member on his own mission. He explores those areas where he is most likely to find snakes and scorpions. Almost immediately he comes across a black scorpion, and calls me to come and take a photograph. He shows me how to “milk” the venom. I watch in fascination as the milky fluid oozes out of the barb at the tip of the tail.

“Have you ever been bitten by a snake?” I ask, morbidly curious. “Countless times,” he answers, “but never by a really venomous one. The closest I came to that was a puffadder, but fortunately it struck against my thumb nail and didn’t cause any real harm.”

Working our way up an incline, the peace of the wild descends upon us, which is probably why, when it comes, none of us immediately grasps the full implication of the words. “Black mamba,” says Ken evenly, as if he’s discussing a cup of tea. “Mitzi, come up here so that you can take a photograph.”

Oddly enough my blood doesn’t curdle. I do not gasp for breath. Instead, I obediently scamper uphill to where Ken is peering intently into a bush. The black mamba is lying on the ground, half hidden by the bush. I take two very shaky photographs.

Suddenly there’s a movement. The bush rustles. Then the mamba shoots out from underneath the bush and disappears down a hole to our right. “We can be very glad that we weren’t between him and his lair,” says Ken.

Resuming our survey we come across a variety of insects, lizards, another two scorpion species, a tailless whip scorpion and a centipede devouring a grasshopper.

Then the allocated time has run out and we make our way back to the SAEON offices. There pictures are downloaded, reference books are consulted, lesser known plant, reptile and insect species are identified and the lists are finalized for the afternoon’s feedback session in Hoedspruit - an impressive 226 species for the aquatic site and 178 for the terrestrial site.

On our arrival at Hoedspruit I get the impression that the entire Lowveld community has gathered there for a mass drumming session. The hypnotic rhythms evoke the earlier history of the region, when the drums told their tales of death, war and the birth of kings.

When the drums falls silent, it is time for the feedback session, and each of the groups is given the opportunity to report on their findings. From the awestruck faces of the international visitors it is evident that they are hugely impressed by our country’s biodiversity.

Cameras flash. Television crews, among them the BBC, are on hand to film the proceedings. South Africa and its rich diversity of life forms will feature on the television screens of people from all over the world.

Thank you SAEON, for the opportunity to attend such a significant and remarkable event!