The case for long-term electronic data archiving

- By Avinash Chuntharpursat, Information Management Coordinator, SAEON

History and principles of archiving

Archiving has been an activity carried out for thousands of years as part of documents and artefact management. Ancient civilisations from across the world have left records of what existed and what life was like during their period of existence (figure1). As in figure 1, the technology used was the most appropriate for the times. This included papyrus, cloth, clay figurines and pots, metal artefacts, paintings, engravings, tablets and a host of others.

|

Figure 1: Clay figurines showing livestock species and the court lifestyle of an ancient Chinese Emperor Liu Qi (188 BC – 141 BC). Note the human figures in front had wooden instruments in their hands (Picture © Avinash Chuntharpursat)

Let’s examine some of the principles of archiving. Archiving for historical purposes serves as a study of the past and from a scientific perspective it also serves to provide benchmarks for the measurement of change.

From figure 1 the clay figurines provide information on what livestock species existed at the time. This information can then be used to assess the state of current livestock biodiversity to work out gains or losses.

It appears that the principles of archiving have not changed much over time, however the technology available to archive has. With modern advances in information technology, archiving has moved to a new media namely an electronic media, and with it comes a whole new set of challenges.

What and how long to archive

According to the principles of long-term ecological research which SAEON is part of, long-term data management including archiving is a critical component. This begs the question: for how long?

This tends to vary from local anthropocentric changes which take a few years to transform a small part of the landscape, to several centuries or millennia during which large-scale climatic influenced changes take place. The “how long” also applies to how long the data should be held. To measure large-scale, long-term changes, data sometimes needs to be held forever or as long as society is around to hold it, which may run into thousands upon thousands of years.

This poses a daunting challenge for archiving of countless records involving climate, soil, water, biodiversity and a host of other data.

It is also a matter of what should be archived for future use. This gets ever more complicated as new fields of research arise. An electronic archive permits a lot more data to be stored relative to the space occupied by the records (versus paper records), but are all the records necessary? The issue of space and dissemination of data/records is a major advantage that electronic archiving has over traditional paper archives.

The recently held 1st African Digital Management and Curation Conference and Workshop on 12 and 13 February 2008 certainly had a strong focus on this subject. The conference started with an inspiring address by South Africa’s Minister of Science and Technology, Mosibudi Mangena, which entailed the ethics of data sharing and benefits of the implementation of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) guidelines on sharing of scientific data produced from publicly funded activities and programmes.

This was followed by several presentations on diverse issues of data curation, but long-term digital archiving was a recurring theme. Various international horror stories on the loss of digital data were presented by several people from across the world. With the data loss came the associated financial loss of collecting that data and the loss of that knowledge to society.

Software and hardware considerations

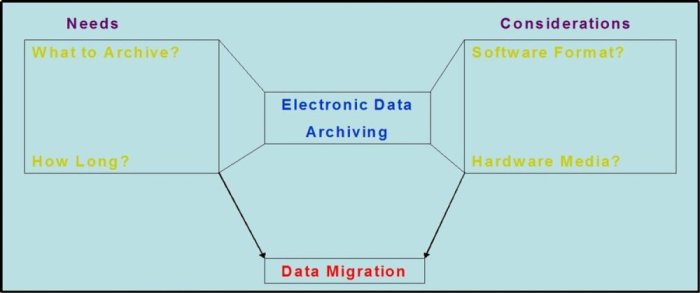

An analysis of the situation revealed that there are two crucial components that need to be synchronised for successful long-term digital archiving. This is the software format that the data is stored in and the hardware media on which the data is stored. Figure 2 shows how these components are integrated into the system.

|

Figure 2: Conceptualising the needs and considerations of electronic data archiving.

The above horror stories on losing data largely involved storing data in a particular software format that has become outdated and inaccessible due to many reasons, such as software companies closing / being taken over or better software becoming available on the markets.

Another reason is that the physical medium that the data was stored on lost its lifespan or changed with advances in technology. Some examples given at the conference include rooms of magnetic tapes which can no longer be read due to changes in hardware. A more common example was the use of 8 and 5.25 inch floppy disks which are unreadable nowadays.

These are the regular pitfalls of digital archiving. However, it is not all doom and gloom. Figure 2 indicates a solution in the form of data migration. Data migration is a term used for the moving of data from one format to the next and one medium to another. In order to successfully accomplish this migration, the electronic archivist needs to be diligent in following any changes to formats and storage media.

Current options

There are numerous software formats to store data and information. There are several commercial packages available for creating documents, spreadsheets, databases, graphics, etc. For long-term archiving purposes, it is not recommended that these proprietary formats be used. Often data in these formats cannot be opened by other software and sometimes the latest version of the software cannot open files made by earlier versions of the same software.

The archivist should stick to the lowest common denominator, i.e. the format that can be read by all (or most software packages). For alpha-numeric data some of these formats include text, ASCII, XML and SQL. However, these formats are not always guaranteed.

Certain commercial software packages insert their own versions or code into these formats. This introduces difficulty in interoperability. Graphic formats include JPEG, GIF, PNG and even large bitmaps if detail is required. Care should be exercised when resaving JPEGs as this reduces the quality of the image. Spatial data formats are a special case, since this field is so recent there is not much of a history of archiving. The Open GIS Consortium (OGC) standards can serve as a guideline; shapefiles are commonly used as well.

In terms of storage media once again there are numerous products on the market. Various hard disk and tape drive solutions are available, as well as CD options. As with the software, there are no guarantees. Currently there are CD formats and DVD formats available. Earlier this year, the acceptance of blu-ray over HD DVD as a new optical disc format has introduced more excitement for the data archivist. There are also storage considerations with these types of media which are not discussed here.

As with the ancient archivist, numerous options are available to the digital archivist. Due to rapid advancements, the digital archivist is at the mercy of the IT industry. It is up to the archivist and the archives to be vigilant and ensure that they remain up to date on technological advances and migrate the data timeously. If not, stick to paper.