ACEP takes a new look at ‘old-four-legs’

|

After an initial expedition in 2005, the African Coelacanth Ecosystem Programme (ACEP)1 returned to Sodwana Bay in May 2011 to find and observe coelacanths and their habitat by means of their newly acquired remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

Known only from fossil records and thought to have died out 70 million years ago, coelacanths were first ‘rediscovered’ in 1938 by the Curator of the East London Museum, Miss Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer when a specimen was caught by a fishing trawler off the Chalumna River. Professor JLB Smith of Rhodes University recognised the specimen as a ‘living fossil’. As the closest relative to the ancestors of all land vertebrates, coelacanths have intrigued scientists ever since.

The robust fish grow to about two metres in length, are a mauvish blue colour with lobed ‘leg-like’ fins and an incredibly small brain, occupying only one per cent of the skull. The little information available on coelacanth diet suggests that they feed on deepwater fish and cephalopods.

Caves and canyons

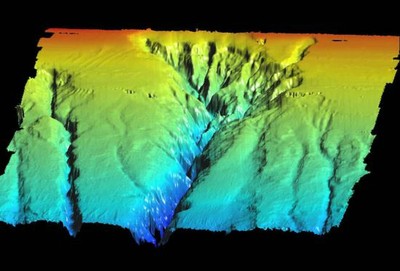

How they could successfully survive for over 350 million years, which makes them the longest lived vertebrate group, and elude scientists has much to do with their habitat. The docile fish have an affinity for caves associated with areas of steep topography such as underwater canyons. In the past, coelacanth have been reported from depths between 54 and 300 metres.

The narrow continental shelf off Sodwana Bay provides scientists with an ideal location to observe coelacanths, as the close inshore region is scarred with underwater canyons. Of these, Jesser Canyon has been the focus of most attention. Here, in 2000 a group of divers using specialist equipment discovered a group of three coelacanths in their cave at 104 metres of water depth. They were among the first of a handful of humans to observe live specimens. However, due to the hazards associated with such deep diving, some divers have subsequently paid with their lives in attempts to see coelacanths in their natural environment.

Deep-water exploration

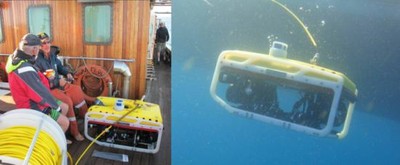

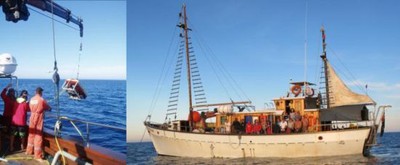

ROVs have the potential to reduce the risks associated with deep-water explorations tremendously, while increasing observation times at such depth from a mere couple of minutes on SCUBA, to several hours a day with a ROV. ACEP’s Falcon Seaeye ROV is relatively small (50 kg), easy to handle and has a depth rating of 300 metres. For this trip it was deployed from the MY Angra Pequena, a 22-metre motor yacht equipped with a hydraulic crane.

Flying the Falcon

After some initial technical problems, the Falcon ROV was ‘flown’ for five days, totalling 12 hours of underwater observation time at depths down to 120 metres. Apart from valuable habitat surveys, the coexisting fish and invertebrate fauna were assessed and sampled.

The observation of a group of four coelacanths in a cave at 110 metres brought matters to a climax. A team of technical divers from Triton Dive Lodge had discovered these particular animals a few days earlier during one of their training dives and their instructor (and deep-diving legend) Peter Timm could guide the ROV pilots to the very spot.

Despite the success of the expedition, time in the field was limited and many questions remain unanswered. In particular the use of the canyon habitat by coelacanths and possible movements between canyons will shed light on the life-history and population dynamics of this fascinating survivor.

Related content:

1 ACEP is a flagship research programme of the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), which also hosts the SAEON Elwandle Node. The programme focuses on the marine environment off the east coast of South Africa. SAEON provides the management system under which the second phase of ACEP is run.

|