Powers of observation in the Botswana bush

|

Tim O’Connor, Observation Science Specialist, SAEON

When advocating the value of long-term environmental observation, the scientific community would usually emphasise how this value appreciates over time for contributing to decision-making. It is a nice position to hold because judgment on the effectiveness of observation can be deferred.

A counter-position is that, notwithstanding the alleged benefits of long-term observation, the financial and human resources it consumes could perhaps be better employed in addressing issues of more immediate concern.

It is therefore instructive to examine a case study in which long-term observation has played a material role in influencing decision-making about an important social and economic issue.

The future of Botswana’s wildlife

I recently had the good fortune to attend a workshop in Maun, Botswana, concerned with the future of northern Botswana’s wildlife. The workshop was co-hosted by the Botswana Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP) and the Southern Africa Regional Environmental Program (SAREP).

Tourism is one of the top four contributors to Botswana’s GDP. This is a relatively small country that is economically not very diverse. It would be socially undesirable to further constrain an already limited economic breadth. The quality of its wildlife experience is a ‘commodity’ that few other African countries can match. But if this quality were to deteriorate, would the country still attract as many international tourists?

Why the concern?

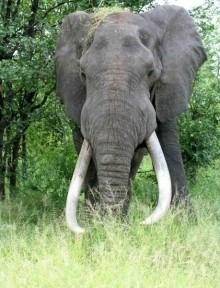

Quite simply, many wildlife species have been declining at an alarming rate in northern Botswana. A number of large mammalian herbivore species have declined over the past couple of decades, including wildebeest, zebra, giraffe, red lechwe, impala, tsessebe, and kudu. Exceptions are hippo and elephants – the population of the latter has increased from fewer than 40 000 to a figure that appears to have stabilised at 140 000 (mainly through emigration to adjoining countries).

A first obvious question is about the reliability of the data. Difficulties in obtaining an accurate or precise estimate of wildlife populations are well known. Northern Botswana is large and can only be censused by air. Fatigue and stomach rebellion are recurrent hazards for an observer. Animals are not as easy to see from the air as a lay person might imagine. Confidence intervals for the population size of any one species tend to be quite large. If only two censuses have been conducted, it may be difficult to make any strong assertion about change.

The power of sustained observation

Herein lies the power of sustained observation effort. The DWNP has amassed about two decades’ worth of wildlife data through repeated censuses. For the statistically inclined, notwithstanding the variability of individual censuses, an analysis of trend over time clearly supported a conclusion of declining populations of a number of wildlife species. Values of an 18% decline per annum for wildebeest, a 60% decline over 11 years for lechwe, or an 8% per annum decline for giraffe were easily accepted with data of this value, as were the population changes of the other species.

Any argument that it was simply part of natural variability and did not therefore demand a response may have accounted for some change, but it would have been at odds with the observed consistent directional pattern of change across a number of very different species. There were clearly other reasons for the declines.

Demonstrating a decline in a wildlife population does not, unfortunately, reveal the causes. But if a response is to be initiated in order to redress these changes, then the reasons for the declines need to be understood. It was beyond the scope of the workshop to resolve this issue in its entirety, but some important principles emerged.

Understanding the causes of decline is only as good as the candidate explanations on offer. The workshop hosted a number of high quality presentations addressing both theoretical and site-specific material on purported causes. These included animal movements and migrations in relation to veterinary fences, disease and epizootics, hunting, poaching, hydrological dynamics of the Okavango Delta, the effect of said dynamics on vegetation, water provision, habitat modification by elephants, altered fire regimes, escalated predation pressure, and loss of key wildlife habitat to land use changes and human settlement.

These purported causes could be partially interrogated on account of the quality of science and immense study effort behind each. A simple lesson was that individual explanations would need to be sought for each of the declining species. Different species are apparently declining for different reasons, and an emerging scientific challenge is to tease out the differences.

But this is subject matter for another time. In closing this article, I would rather concentrate on the key lessons about an approach to observation I thought this exercise had demonstrated.

Key lessons

First, a mandated authority upheld its clear commitment of maintaining wildlife census over time. Without this hard data there would simply have been claims and counter claims as to whether wildlife was declining. Plus the monitoring had been well conducted and the data are therefore of good quality.

Second, the data had been used in formal analyses in order to assess whether there was cause for concern. The workshop was the result of these analyses. I am aware of many a monitoring data set in South African conservation areas that have not been subjected to any formal analysis. What might have been averted or promoted had they been undertaken?

Third, organisations and academia have made a substantial contribution to additional monitoring over time that assisted in interpretation of trends. ‘Elephants without borders’ contributed an invaluable recent census that could be undertaken beyond the mandated area of the DWNP.

Exemplary records of elephant trophy hunting in northern Botswana have been maintained over many years by a hunters' association – the resulting modelling exercise of population changes in tusk size was spellbinding.

The University of Botswana's Okavango Research Institute in Maun has contributed input including remote sensing of environmental change, effect of hydrological changes of the Okavango Delta on its vegetation, and animal movements in relation to key resources, amongst other things. The persistent efforts of other academics have helped to unravel issues such as the dynamics of a guild of predators in relation to prey availability, and zebra movements in relation to environmental and biotic factors. Local operators have consistently contributed hard data on poaching effort for their areas.

Strong knowledge base

Collectively these efforts provide a strong knowledge base for informed decision making. The matrix that provides real value to their efforts is the baseline information on population trends of wildlife.

Finally, the process was transparent. The issues and information are out on the table. The potential for any interested party to contribute is there. A broad input has been sought. Personal agendas can be kept in check.

This augurs well for considered decision-making by responsible parties that will meet the needs and aspirations of the people of this country.