Using the past to manage the future

|

What is palaeoecology?

Understanding the past is important if we are to interpret today’s ecological processes and predict future outcomes. Records of past environmental change are found in lake sediments, peat bogs, and other wetland areas where organic material and minerals accumulate over time in anaerobic conditions.

Fossil pollen, diatoms, spores and charcoal are preserved in the sediment and provide records of past vegetation, climate, herbivory and fire history. Sediment cores are extracted from wetlands using drilling equipment. The sediment samples are treated in the laboratory with strong acids and bases, leaving only biogenic materials (fossils) that can be identified, counted, dated and linked to ecological processes.

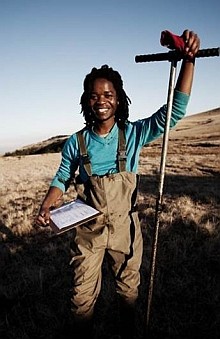

Briefly, that is what palaeoecologists do and where the fun happens! In the case of my project, cores were collected in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and the pollen extraction occurs at the palaeoecology laboratory in the Plant Conservation Unit at the University of Cape Town (UCT).

Some people ask why we do what we do – which involves collecting sediment from muddy places infested with tall grass and leeches (and sometimes even crocodiles!). The short answer is that we love what we do and our passion for knowledge does not discriminate between environments ... well, except in rare cases.

The project

My work is part of a larger project run by the Plant Conservation Unit and funded by UCT’s African Climate and Development Initiative. Entitled “Benchmarks for the Future”, the aim of the project is to combine long term data from palaeoecological and historical changes to understand how different drivers of vegetation change interact.

We are particularly interested in what happens at ecotones – the boundary between two distinct vegetation types - because it is here that plants are at their ecological or physiological limits and vegetation is expected to be most dynamic.

The SAEON Grasslands-Forests-Wetlands Node provided support towards the field work component of my project, entitled “Reconstructing palaeovegetation sequences at biome boundaries in KwaZulu-Natal province in the late Holocene”.

In November last year, my team and I had the privilege to travel to the KwaZulu-Natal province on a coring expedition to collect samples for my PhD project. The road trip to KZN from UCT was long, interesting and packed with biodiversity contrasts. From the low-lying Cape, up the bare flat-topped hills of the nama karoo, high up into the grasslands of the Free State, and then a roller coaster ride down the dissected hills of KZN decked by either grasslands, forests or savanna elements.

From November to December we shared smiles and mishaps, drank plenty of juice, worked hard - from Ithala Game Reserve down to Umgeni Vlei and up into Hluhluwe-Umfolozi under the guidance of our strategic partners.

Julius Caesar would have said, “We came. We saw. We conquered.” But we came, we saw, we cored ... and appreciated the immensity of what we do not yet know and took responsibility for the tasks ahead of us. Our motto is that when you see an “interesting” site, core it!

The Big Picture - Climate change and biodiversity loss

Although there is much uncertainty in the science regarding the future in changing environments, a point often cited by sceptics, improvements in available tools and knowledge provide many opportunities for understanding our complex environment. Issues like the anthropogenic link to climate change are still being debated even though the science has radically improved and most people in the scientific community are convinced.

Reconstructing the past helps to bring into perspective long-term evidence of environmental change, ecological processes and the role of climate and other drivers of vegetation change. Positioning science within our complex societies, with multiple views, stakeholders, and levels of scientific understanding is a challenge that must be addressed if we are to be effective in addressing fundamental issues on environmental change and biodiversity loss.

Collaboration

My research is part of a palaeaecology project initiated by ACDI (L'Agence canadienne de développement international) and supervised by Associate Professor Lindsey Gillson and Professor William Bond of the Plant Conservation Unit at UCT. Our partners include the SAEON Grasslands-Forests-Wetlands Node and Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, and we acknowledge the farmers who gave us access to their property and Mazda Wildlife Fund for sponsoring the use of their vehicle.

We are in the process of establishing ties with individuals and organisations so that we can share knowledge, experience and resources in the interest of better understanding our environment to improve its management. I wish to thank the above contributors for their sterling work. Ms Sue van Rensburg of SAEON deserves special mention for bringing together many of the pieces in the end.

|