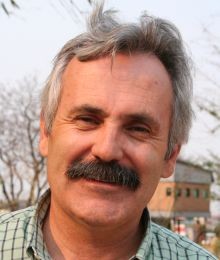

Dr Manuel Maass shares his views on the Mexican approach to LTER

|

The natural environment in which we live is complex and interrelated. As American naturalist John Muir pointed out, when one tugs at a single thing in nature, one finds it attached to the rest of the world.

It is this principle that lies at the core of the Mexican Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network’s approach to environmental research. Based on the nature and complexity of the natural system, the Mexican LTER network participants opted for a systems approach rather than a process approach in their research.

During an interview with SAEON eNews, Dr Manuel Maass of the Mexican LTER explains that there are two types of ecological research -- one that focuses on the process and one that focuses on the system. Scientists traditionally focused on a single process such as soil erosion, rainfall or energy fluxes, and studied that one process in a number of different systems. This approach led them to an excellent understanding of the particular process and the context in which that process took place, with the result that they came to be regarded as experts in the field. Even today a large contingent of scientists all over the world still focuses on processes.

“But focusing on processes has its limitations,” cautions Dr Maass. “To understand the complexity of the natural system we cannot afford to study one process only. There is a multitude of processes involved, so the more processes we study in a particular ecosystem, the better our ultimate understanding of the system.”

Teamwork is crucial

For a systems approach teamwork is crucial as researchers depend on the shared information. Dr Maass is a firm believer in a multi-disciplinary approach to research. “We need people from different fields and institutions collaborating; we need to study collateral; we need to involve people like engineers and social scientists working along with ecologists,” he argues.

In organising a team of researchers, he opts for interdisciplinary researchers who will look at the issue from many different perspectives. The rule is not to start off by finding the best qualified people available independently of what they do, he says, but rather to look at what needs to be achieved and then get the best team together for that. The team members also need to be evaluated beyond "traditional” aspects, for instance on their communication or teamwork skills, hence the qualifications of the team members may vary considerably.

“In a collaboration such as this you have a number of properties emerging which add to your understanding of the system, and it is a lot of fun,” Dr Maass says with a grin. “You find yourself swimming in rough seas at times, you face uncertainties, you dive into complexity, but you are not alone. This approach depends on collaboration.”

He mentions that the goal of understanding the product is complex in systems thinking. It has to be, as a simplistic approach will lead nowhere – the researchers will never reach the level of understanding they’re aiming at by breaking the problem down into small parts and then trying to understand the parts as separate entities. The whole is much more than the sum of the parts.

Holistic perspective

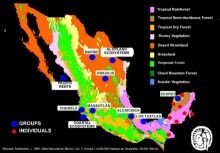

Mexican LTER researchers are encouraged to work holistically, moving to focusing their study on a whole region instead of on a particular site. System thinking is a relatively new approach. Back in the 1960s, for instance, there was no consciousness of the ecosystem services concept in Mexico -- Government considered tropical areas as wasted land that had to be opened up to agriculture through deforestation, and assisted local settlers with ecosystem transformation. As a result, large areas of tropical forest were converted to maize fields and pastures.

So the scientists decided to study the impact of that transformation in an effort to understand the processes behind ecosystem services. It is becoming clearer that ecosystem processes occur on different scales – some take place in an area of a few square metres while others take place in an area of hundreds or thousands of square kilometres. “The problem comes if you mess with these processes, if you start changing things without understanding what you are doing to the system,” says Dr Maass, adding that by attempting to transform the system one could actually be degrading the system.

He compares the situation to the hen that lays the golden eggs. The hen doesn’t complain much when the eggs are taken, but eventually stops laying eggs altogether.

“I think that behind the current serious environmental crisis we are facing is our lack of understanding of important ecosystem processes that take place in the long term,” he says. “We don’t mean to destroy our environment, but all the same it took us seventy years to realise what we’re doing to the ozone level, for example.”

He adds that there is an ethical component to all of this -- knowing that what you’re doing is harmful to the environment and yet you continue doing it, like mining in protected areas.

Adaptive management

We need more evidence about the effect of our actions, and about the impact of climate change, but while we’re still dealing with uncertainly it would be wise to follow a precautionary process. That is what lies at the essence of adaptive management.

“We as scientists need to produce data for creating a conceptual model of how these natural processes work and then, based on that, we can predict and make decisions,” he explains. “That is where the importance of long-term monitoring comes in – we need to monitor the effect and consequences of what we are doing; to see if there is a match between what we think is going to happen and what is actually happening. If these match, we know we are on track. If they don't match, we need to rethink our management strategy and adapt it according to the results. With every management cycle we reduce uncertainty and keep working on refining the model.”

In the past, the science system world wide promoted short-term studies linked to limited time and space. This lies at the root of our current limited understanding of ecological processes and this is exactly why an LTER network is so important.

Although LTER is well known nowadays, it only gained full recognition over the last couple of decades. Back in the 1990s the well-known scientist Harold Mooney, President of the Ecological Society of America, said that even if we reviewed the last ten years of our best ecology journals we would not be able to recognise an imminent environmental crisis, as most of the research had been done at a level that would not show that. He stirred the whole ecological fraternity by saying that environmental scientists needed to change the way they do research.

This doesn’t mean that we don’t need short-term research, Dr Maass explains, but we also need research that deals with complex systems, large-scale research with a long-term focus. That is the challenge behind LTER.

The Mexican LTER Network

With Mexico being a country without the kind of money and human resources found in countries such as the US, it took several years and a tremendous effort to launch the Mexican LTER network.

Without a bag of money to foster the process, the small group of dedicated scientists started the process with the limited resources they had at their disposal at the time and asked themselves how they could develop a dream network. “We conceived the Mex-LTER network as a large environmental assessment instrument (like a telescope) which would allow us to deal with our most pressing environmental research questions,” Dr Maass says. However, this required the coordinated effort of a large number of scientists, in multiple sites and over a considerable period.

Dr Maass gave numerous talks to convince scientists to join in the effort and the very first question they invariably asked was how much money had been allocated to the initiative and where the money would be coming from. He told them that while he couldn’t guarantee that they would get money, he could guarantee that the chances to get money would increase exponentially if they got together and got started. And he was right – the funding did eventually materialise and is increasing exponentially.

Nowadays increasing numbers of scientists are convinced that LTER is the way to go. The big problem Mexican LTER is currently facing is a human problem – how to implement LTER. “We need groups of people working together,” Dr Maass says, “and we need to build relationships with fellow scientists. What is required is a certain state of mind, the ability to communicate, the human qualities towards teamwork.”

The Mexican LTER Network collaborates with research groups that study terrestrial and aquatic Mexican ecosystems. Dr Maass emphasises the fact that the Mex-LTER network is a group network, not a site network. However, each group is strongly associated with a site, where ecological studies are developed following the core research areas, and long-term monitoring is done of key ecological and environmental variables.

Dr Maass was elected first Chairperson of the Mexican LTER Network in 2004, and served in that capacity from 2004 to 2008, followed by a two-year period as Co-chair. Although that period has since come to an end, he will remain an active member of the network.

He is also currently a member of the Executive Committee of the International LTER network.

Future perspective

Dr Maass is adamant that scientists need to ensure that the knowledge and understanding gained from their research should be translated into policy recommendations. Research results must be implemented, and the effect of the implementation must be monitored. Yet this is seldom done. To address this problem the implementation process ought to be part of the evaluation or rating of scientists, not merely the “publish or perish” kind of criteria, he argues.

“Even though Mexico has some of the best environmental laws in the world, we still have environmental problems,” says Dr Maass. “How many of these laws are actually applied and implemented? Another reason why feedback and long-term monitoring is so important.”

In conclusion Dr Maass mentions that the Mexican LTER Network subscribes to ILTER’s vision of a world in which science helps prevent and solve environmental and socio-ecological problems.

“We as scientists need to make a concerted effort to ensure that science does in fact help prevent and solve these problems,” he says.