Feathered harbingers of South African power consumption

|

When it comes to monitoring and studying a single species, the question may well be asked: Why expend considerable resources studying this species when there are so many complex issues awaiting our attention?

It is easier to justify concerted effort of this nature when Red Data species are involved so that our children may know them, but I wish to highlight in this article that monitoring of such species can also produce quality observation science and inform us of how observation should best be conducted.

The example in question is the Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), a denizen of the high Lesotho plateau and adjoining Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa.

This 6 kg monarch of the montane skies lives for about 20 years, but only commences breeding at seven years of age, a monogamous pair attempting to raise a chick mostly every year. Reproductive output is therefore low, juvenile mortality can be high, so that a high survival rate of sub-adults and adults is essential for population persistence. This is a common pattern for many species of large, long-lived birds.

There has been cause for concern about Bearded Vultures for some time. The estimated breeding population in the 1980’s of about 200 pairs had shrunk to about 100 pairs by 2012. This is the total southern African breeding population. A large perturbation of the population might well jeopardise its continued existence.

Understanding population changes

What are the knowledge requirements for understanding - and thus anticipating - population changes of this species? Projecting population change through the use of a population model requires an estimate of population size, age and sex structure, and survival and fecundity. Such information has been acquired through the hard slog of repeated censuses.

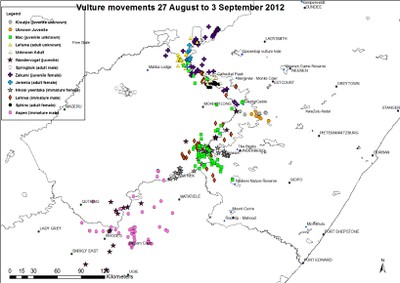

Understanding the pressures which might come to influence a population also requires knowledge of where and when individuals go. This was nigh impossible in days gone by for a bird that could comfortably cover tens of kilometres in a day.

All scientific advancement is constrained by available technology. Development of satellite tracking was a turning point. Although transmitters were initially too heavy and bulky even for a bird as large as a Bearded Vulture, further technological advancement has rendered them suitable. Plus we now have fancy software for display and analysis of spatial movement patterns.

Sonja Krüger of Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife is conducting research on the Bearded Vulture with a view to providing the knowledge required for conservation of this species. Birds fitted for satellite tracking are an integral part of her approach, but this species nests on high precipitous cliffs and adults are difficult to catch. Nonetheless, both had to be attempted if the study was to succeed.

Sonja offered me a ‘blast from the past’ experience of accessing two Bearded Vulture chicks on their cliff eyries in the Cathedral Peak area of the Drakensberg. (I had co-ordinated a ringing programme for Cape Vulture nestlings on their krantz homes whilst a university student.)

A fresh November morn, the Berg carpeted with snow, and it took 15 minutes for the helicopter to alight on the top of the escarpment (Berg hikers will understand). A long and hard day increased the sample by two, all that funding could allow. Adults have also been trapped at feeding sites and fitted.

The chicks eventually fledged and commenced their life’s journey. It is intriguing to follow the travels of an individual bird with which there is a personal affinity. Adults sit tight in their territories, but juveniles traverse the range of the species repeatedly in the course of a year.

The value of monitoring

An acid test of the value of monitoring is whether it can contribute to answering questions when change takes place. Already facing many threats, the latest for Bearded Vulture is the erection of wind turbines along the top of the Drakensberg escarpment and at various localities within Lesotho for generating electricity to sell to South Africa.

Studies in Europe have shown that populations of large birds such as vultures and raptors can be decimated by wind turbines - a quarter of a Spanish population of European Griffon was lost within a year. Would Bearded Vulture be similarly impacted in Lesotho? Could this be a tipping point for this species on the road to extinction?

Satellite tracking records the altitude above ground level at which birds fly, which is coincident with the span of rotor arms. It is a double whammy for the population. Adults whose territories encompass a wind farm site face an increased likelihood of death - about 20 % of nesting sites may be affected. In addition, almost all juveniles and sub-adults can potentially be impacted by wind farms during their six years of extended travel. Population modelling indicates that this level of impact is not sustainable.

I discerned some key principles for monitoring from this exercise. The use of models is essential both for understanding population behaviour and for projecting the effect of novel impacts. Hard slog work such as determining the number of nesting pairs provides an essential foundation - we need more field work and fewer desk-top studies.

Advances in technology can reveal insights which would not previously have been attainable. These challenges are tractable with a single species such that a process-level insight can be gained - comparable efforts for a community or system are extremely difficult to achieve.

But most important of all, success requires a champion of the cause.

|