How is the lower Olifants River doing? Insights from six years of river health monitoring

|

The upper Olifants River has received much attention from government and the media over the past decade, due to the problem of acid mine drainage from old coal mines on the Highveld (click here for a recent report).

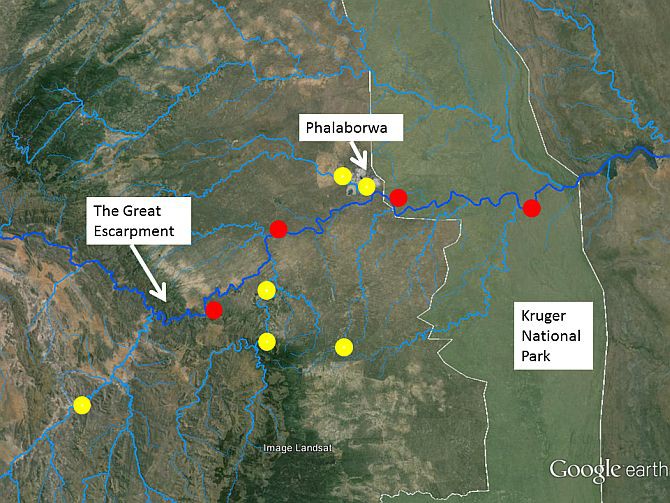

The lower Olifants River, hundreds of kilometres downstream of that source of pollution, flows primarily through protected areas and has maintained reasonably good quality to date. However, local sources of pollution in the Lowveld, from agriculture, towns and the Phalaborwa mining-industrial complex have always been a concern.

Are current monitoring methods adequate?

In 2009, the SAEON Ndlovu Node initiated a long-term research project that aimed to investigate whether the conventional monitoring methods employed by South African National Parks (SANParks) and the Department of Water Affairs and Sanitation are adequate for detecting deterioration in water quality of the river, as well as causes of any such deterioration.

|

|

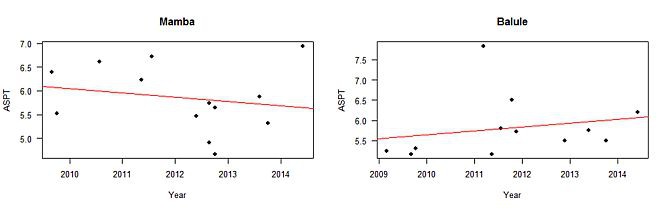

Standard monitoring methods have been applied more frequently, and at a greater density of sites, than the standard monitoring programmes, to determine how much seasonal variation occurs in the variables measured (particularly the SASS5 metrics), and whether the standard methods are actually able to detect trends given the long sampling intervals (of one to three years).

Monitoring data show no deterioration in water quality

A spin-off of this research is that an unusually dense time series of monitoring data is now available to assess trends in the state of the lower Olifants River over the past six years. The good news is that our data indicate no deterioration in the quality of the water in the Olifants where it enters the Lowveld, and at three sites downstream including two in the Kruger National Park (KNP).

Furthermore, macro-invertebrate communities within the river in KNP appeared to have recovered rapidly from both the severe flood (in 2012) and the large spill of acid waste water from a Phalaborwa phosphate plant (in 2013, reported on in SAEON eNews in February 2014.

|

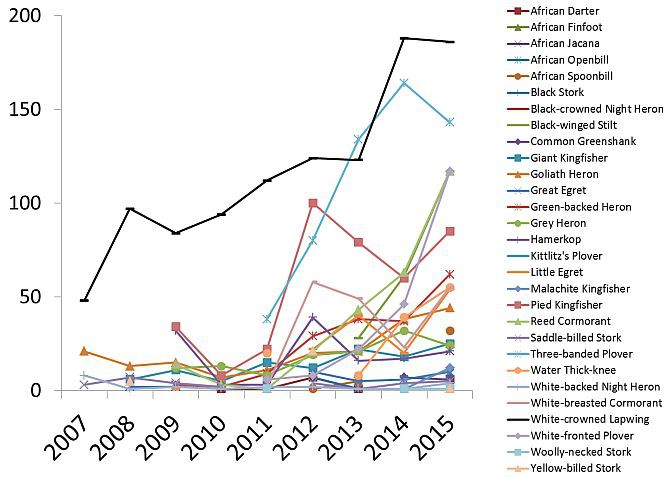

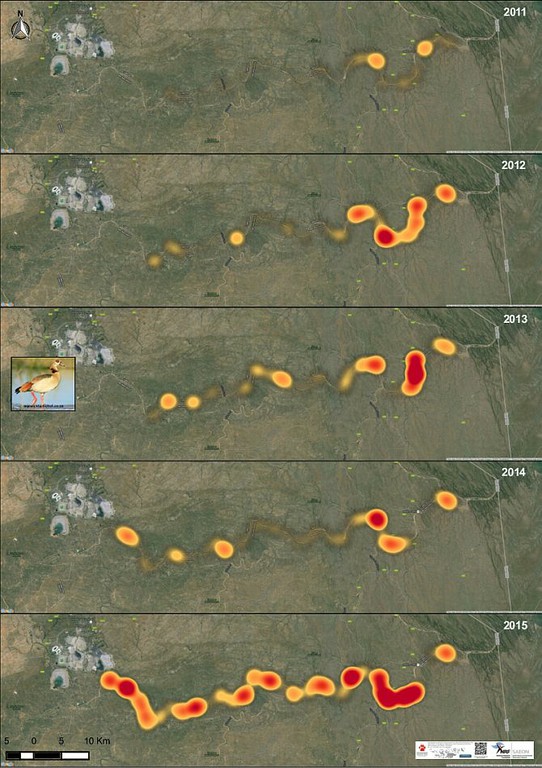

A very different source of data, of sightings of river-dependent birds recorded during annual river walks, supports this conclusion. These data, kindly supplied to SAEON by the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) indicate increased abundances of most bird species along the Olifants River, within KNP, over the past nine years.

|

But all is not well…

The bad news is that there are signs of deterioration of the Blyde River, a key tributary of the Olifants in the Lowveld that provides an important input of clean water. In addition, the Selati River, another major tributary, remains in a severely degraded state and continues to feed highly polluted water into the Olifants just before it enters KNP.

Two other clues that all is not well come from two unconventional sources. Firstly, the EWT’s river bird monitoring data indicate an exceptional increase in Egyptian Geese over the past few years.

|

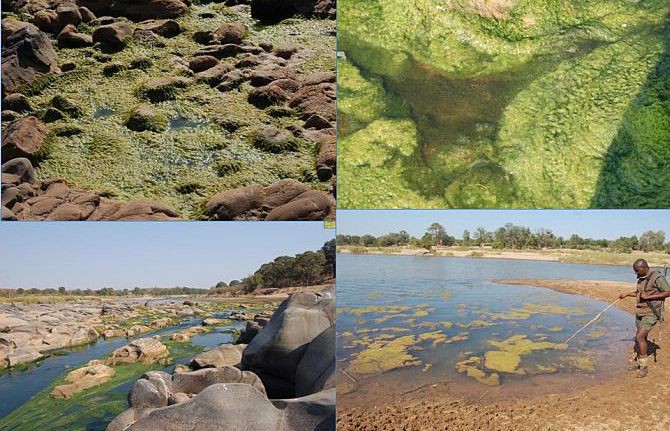

Moreover, the cover of filamentous algae appears to be increasing, with large parts of the river coated in algae during periods of low flow. Both these emerging patterns indicate a problem of eutrophication - a problem that so far has not been detected by the standard monitoring methods used in the project.

|

These results indicate that key changes occurring to the chemistry and biota of the river over recent years have not been captured. New methods are needed, and SAEON will be hosting a special session at the SASAQS conference to get input from aquatic scientists working in the region on what research is required to determine the causes and consequences of these emerging problems, and develop more comprehensive monitoring techniques.