El Niño-La Niña cycle needs watching

|

La Niña, the abnormal cooling of Pacific Ocean surface temperatures, is as powerful as her brother El Niño and the effects of global warming on their cycle need to be monitored, UK scientists said.

The La Niña weather pattern could prevent sweltering summers across the world this year, although it has also been associated with flooding in Asia and could bring more hurricanes to the Atlantic Ocean, according to forecasters.

"La Niña is just the flipside of El Niño, it's a cycle that goes around," said weather observation scientist Matt Huddleston.

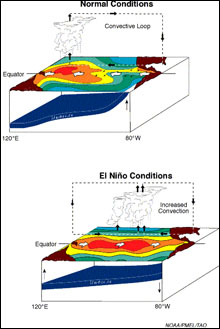

"It's the biggest phenomena after the seasons. It's a natural cycle of warm water moving backwards and forwards across the Pacific, causing a lot of storms, a lot of atmospheric activity that has impact all around the globe."

The better-known El Niño refers to an abnormal warming of surface waters in the eastern Pacific. It tends to occur every two to seven years and lasts for several months.

Forecasters warn that if the El Niño-La Niña cycle were disrupted, the effects could be devastating.

"Some people have even linked the rise and fall of civilisations to persistent El Niño phenomena in the past. If that balance did change, the impact on some communities could be catastrophic," Huddleston said.

The El Niño was widely credited for restricting the impact of hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean last year, and despite triggering floods and droughts like its counterpart, both parts of the cycle are important to global communities, Huddleston said.

La Niña tends to follow the El Niño pattern. In 1997-1998, the biggest El Niño on record killed thousands of people.

"People have talked about mega El Niños where if it gets stuck in a very strong phase it could have an incredible impact," Huddleston said.

The Met Office pays close attention to the cycle when making global forecasts. "Much research goes into connections between El Niño and La Niña and their global impacts," climate scientist Richard Graham said.

One worry among some forecasters is that global warming could disrupt the balance between the two parts of the cycle. "That's the killer question. There is not such a global consensus amongst scientists on the actual impact of global warming on El Niño and La Niña," Huddleston said.

"But global temperatures are warming, sea temperatures are warming, so we may experience more El Niño -like conditions even though that natural cycle continues."

"We need to keep an eye on it," he added.

Source: Reuters News Service