Of coffee and vegetation change

|

Jennifer Russell, Postgraduate student, School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal

“When their scouts saw us making coffee under the trees at the side of the spruit, where it was cool and pleasant [Oom Schalk Lourens said], they turned back to the main army and told their generals about us.”1

These words came to mind as a result of a comment from Sue van Rensburg, Coordinator of SAEON’s Node for Grasslands, Wetlands and Forests. We were crouched under a large Acacia sieberiana trying to shelter from the driving rain, speculating where all the trees had come from.

Sue hypothesised that over a hundred years ago a group of Boers were sitting on these very rocks, grinding up some Acacia seeds as a poor substitute for coffee, watching the Zulus and British fighting it out at the mission station of Rorke’s Drift. Some of these seeds, Sue continued, would have escaped from the coffee grinder and we see the result today: trees, where 130 years ago there were none.

Like Oom Schalk Lourens and his compatriots, Sue and I then moved our locality, but unlike those doughty Boers, we headed for the nearby hotel for a stronger type of coffee.

Changes in vegetation since the Anglo-Zulu War

Flights of fantasy, maybe, but Sue and, earlier, Beate Hölscher (Research Administrator at SAEON), were on a serious mission. They had joined me on my project based in the Umzinyathi district, more specifically, on the battlefield sites of Isandlwana, Rorke’s Drift and Fugitives’ Drift, where I am studying the changes in the vegetation since the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. The work is for a post-graduate degree through the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Pietermaritzburg) and has been registered with SAEON.

The interactive vegetation maps on the SANBI website2 show that this area encompasses the interface between savanna and grassland biomes. Within the grassland biome one finds Income Sandy Grassland and KwaZulu-Natal Highland Thornveld. The savanna comprises Thukela Thornveld.

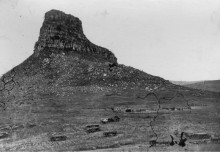

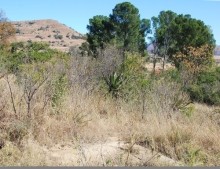

Old photographs tell a story

When one looks at photographs taken of the battlefields in 1879, one is forcibly struck by the lack of woody vegetation. In the accounts written by survivors of these battles, they often emphasise the need to find sufficient wood for camp ovens. They also write about riding through open terrain where now it is so woody one cannot force a passage on horseback and only with difficulty on foot. Inevitably, it poses the question: why - what has happened over the last 130 years to bring about these changes?

The first part of my field work has been documenting the change photographically, using fixed-point repeat photography techniques. This required studying the historic photos, locating where the original photographer had set up his (and sometimes her) camera, and photographing the same view. Using a photo editing programme, one then crops the modern photo to exactly match the historic one. One can then quantify the changes.

I have also acquired a series of aerial photographs from National Geo-Spatial Information, Mowbray, which covers the whole area. These photographs give an indication whether the changes are general and whether the changes are linear or not.

The next part of the field work is floristic sampling. This is where SAEON has come to my assistance in the persons of Beate (a closet plant collector) and Sue. They were to be my technical assistants and I leaned heavily on their expertise.

Beate arrived for the first week of the field trip. We used the Whittaker Plot Method3 and, together, Beate and I braved dense stands of A.karroo, sultry heat and icy hailstorms all in the name of science. Beate also collected a vast number of plants which we pressed each evening for later identification.

Sue arrived for the second week. We continued in the same vein, but at this point the sultry heat turned to chilly rain. We have sampled the woody species in a number of plots at all three sites which cover the grassland and savanna biomes. However, because of the early spring burn in all the sites, we will need to return at the end of summer to sample the grass species.

Who are the culprits?

All this, of course, is important for understanding which woody species are responsible for encroachment and patch thickening. It also provides a baseline for areas that have not, as yet, undergone woody ingress. After that comes the hard part: analysing the data, quantifying the changes and, of course, writing it all up.

I am most grateful to SAEON for embracing my project with such enthusiasm and for the technical assistance provided by Beate and Sue. I look forward to being able to discuss my results with them, particularly over coffee, even if not brewed under a thorn tree.

Jennifer Russell is a postgraduate student of Professor David Ward.

1Bosman, Herman Charles (2000). Karel Flysman. In The Rooinek and other Boer War stories. (ed. C MacKenzie), pp 48 – 53. Human & Rousseau, Cape Town.

2Biodiversity GIS (2011)

3Schmida A (1984). Whittaker’s Plant Diversity Sampling Method. Israel Journal of Botany, 33: 41-46