Following supersonic whispers across Hakskeenpan

|

Hakskeenpan has become synonymous with land speed racing in South Africa.

Since 2010 a British team has been preparing the pan to attempt a new world land speed record over 1 600 km/h in the Bloodhound SSC, a 33 000 horsepower jet- and rocket-powered supersonic car. Dry pans are generally favoured for such events due to their vast, hard, flat surfaces.

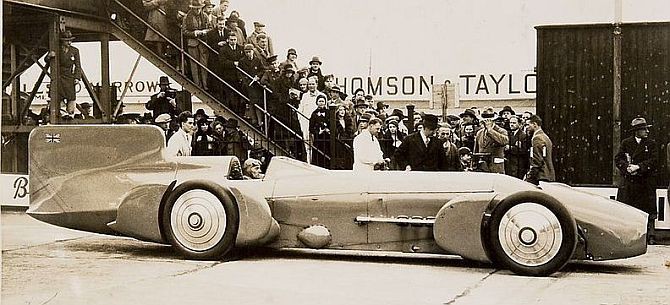

The Bloodhound endeavour evoked the unsuccessful attempt of Sir Malcolm Campbell to break the land speed record of 371 km/h in his Bluebird on Verneukpan in 1929. His nemesis - numerous small rocks scattered across the pan’s surface that slashed his tyres.

For this reason, the Bloodhound team left no stone unturned on Hakskeenpan. In fact, 16 000 tonnes of stones have been removed manually to smoothen the 22 million m2 (20 km long and 1.1 km wide) track in preparation for the race that is due to take place later this year. This remarkable task has been applauded as a significant contribution in uplifting the local Mier community.

|

However, what about the actual racetrack itself - the Hakskeenpan wetland?

Bloodhound boasts state-of-the-art science to be used in the race across Hakskeenpan, but no attempt has been made to conduct state-of-the-art research on the wetland and associated biodiversity, despite annual inundation. Pans in the Northern Cape have been shamefully neglected based on the erroneous assumption that their bare surfaces are lifeless when dry, though the Bloodhound team did express appreciation of inundation after rainfall events:

“Having the desert flood like this is very good news for us, as flooding helps to repair the surface from any damage that may have been caused… and it helps to create the best possible surface for land speed record racing.”

|

Studying the ecology of dryland wetlands

In August 2016, Dr Betsie Milne of SAEON’s Arid Lands Node embarked on a project to study the ecology of dryland wetlands in order to determine the ecology and sensitivity of these periodically wet and dry ecosystems and how they may be affected by (and serve as indicators for) global change and land-use changes. At first word that the Kalahari region has received more than the annual rainfall of 200 mm in January this year alone, a number of freshwater specialists keen to partner with SAEON in the pans project, identified Hakskeenpan as a key opportunity for collaborative research.

Betsie Milne and her team (Gariep Bird Club member and photographer Brian Culver as well as Tshililo Ramaswiela and Joh Henschel from the Arid Lands Node) opportunistically journeyed the 650 km to Hakskeenpan to conduct the first-ever survey of aquatic life on the pan. They undertook a follow-up visit in March after more rain had fallen, suspecting that life-cycles and productivity on the pan had advanced in the seven intervening weeks.

|

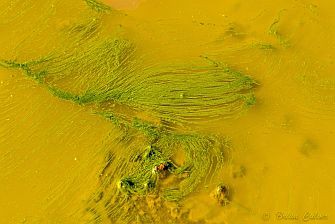

It soon transpired that in 2017 the 15 000-ha pan surface was not fully inundated and water primarily accumulated in the north, while the southern section of the pan had remained dry. This offered an opportunity to not only sample the aquatic communities, but to also include a survey of the shore life and other habitats provided by the desiccated surface (see examples in accompanying pictures).

Stones were green with microalgae, as was the clay, and the water writhed with many species of freshwater shrimps, water fleas and aquatic beetles. Likewise, the shore was rich with different flies, frogs, beetles, springtails, spiders and mites.

Remarkably, some of these terrestrial species also lived on and in cracks of dry clay far from any standing water or ground moisture. Furthermore, in the dry clay were millions of eggs and dormant forms of life, waiting for the next inundation. Watch this space for our analyses of this plethora of life.

|

Therefore, don’t judge a pan by its cover, imitate Joh Henschel and fasten those knee pads to follow the supersonic whispers of organisms hiding under rocks and in the cracks of Northern Cape pans.

Further reading:

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||