Of trawl nets, historical baselines and Gilchrist's hidden legacy

|

South Africa's first officially appointed marine biologist, Dr John D.F. Gilchrist, left behind a scientific legacy that is far greater than may at first be obvious from his numerous publications and reports.

These contributions have lain dormant on the shelves of libraries and archives, remaining unexplored and all but forgotten, until recently. I am referring to vast lists and tables of data, which record the exploration of our offshore marine environment and describe its initial exploitation during the first half of the 20th century. Details of these historical marine data are described in a partner article in this newsletter.

Understanding the past to manage the future

The collection of these data was initiated by Gilchrist and continued after his death, in 1926, by his successor, Cecil von Bonde. Their recent re-discovery and digitisation is poised to provide researchers and fishery managers with a far better understanding of what marine ecosystems looked like in the past and how they might have changed during the last century.

|

Piecing together the historical backdrop of our marine environments is a vital component to the effective management of current and future marine ecosystems. For how can we understand changes in our marine environment, let alone disentangle their causes, if we do not understand where the population or system has come from?

The study of these historical reference points, frequently referred to as 'baselines', is extremely important and feeds into a range of research disciplines: they are required to assess ecosystem change; they are critical in many fishery stock assessments; they are used to initialise ecological models; and perhaps most importantly, they provide reference points to resource managers, conservationists and policy makers, in order to counter 'shifting baselines' – the propensity for successive generations to accept an increasingly impoverished natural environment as the norm.

Exploring past changes

For my PhD research, I am using these historical datasets to explore how parts of the ecosystem might have changed between the early 20th century and the present, and to estimate some historical reference points for certain fish resources.

As a result, I had the privilege to attend the ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea) working group on the history of fish and fisheries (WGHIST) in the scenic Italian village of Panicale from 7 to 11 October. This working group aims to bring together fisheries scientists, marine biologists and historians in order to promote multi-disciplinary investigations into the long-term dynamics of fish populations, fishing fleets and catching technologies.

The meeting provided an effective platform to interact with a diverse set of researchers from across the world who are investigating similar questions, but approaching these using a variety of techniques and data.

Having presented my PhD plans and gained valuable input in Italy, the next stop was to spend four weeks visiting CEFAS (Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science) on the east coast of England. This government research centre overlooks the North Sea in the coastal town of Lowestoft and houses roughly 300 staff working in marine and freshwater environments.

|

Tracing its roots to a small fisheries laboratory established in 1902, CEFAS has accumulated a rich historical legacy, including an outstanding library collection of old, irreplaceable books, journal volumes and reports. If you are searching for information on the history of fisheries or fishing gear, this is a great place to visit! Thankfully I had the kind assistance of Dr Georg Engelhard to act as my host and guide at CEFAS. Having researched these topics for a number of years, Georg has amassed valuable knowledge of historical fishery and fleet dynamics that will no doubt be called upon in future collaborations.

Revisiting the past

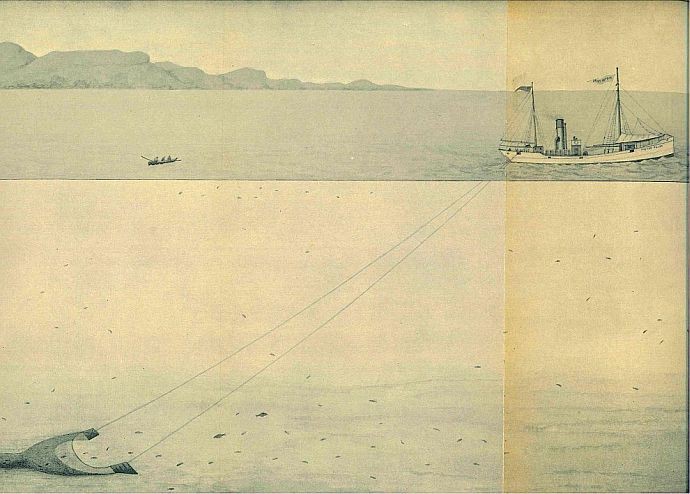

Much of the four weeks in Lowestoft I spent searching through the library and archive shelves at CEFAS. My effort was focused on piecing together information on historical trawl gear from the late 1890s and early 1900s, the period when the Pieter Faure was active as a research vessel in South Africa.

The early period of Gilchrist's investigations is of special interest to us as it offers a globally unique situation - detailed research surveys of an environment that until then, would have experienced minimal human impacts in the form of climate change, fisheries pressure, pollution or the introduction of alien invasives. The great majority of marine ecosystems globally were exposed to decades, if not centuries, of exploitation before being investigated by scientific survey.

My search for historical net details is driven by a plan to revisit sites surveyed by Gilchrist and the Pieter Faure, and to examine these sites by re-enacting the trawl gear and methods used by them approximately 115 years ago. Such experiments will allow us to describe what the fish community looked like back then and assess how it might have changed during the intervening century.

While Gilchrist pronounced that his newly commissioned research vessel, launched in Glasgow in 1897, was fitted with an "otter trawl of latest pattern with all accessories", he frustratingly did not provide a detailed description of this net (at least not one we have managed to find so far). So after having canvassed the local archives and libraries, it was time to move my search to the UK, where much of the history of trawling evolved.

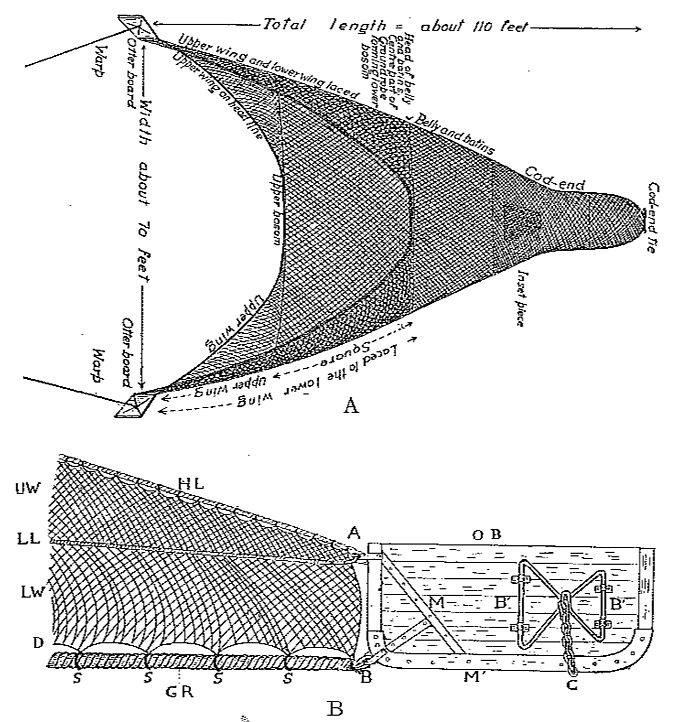

Otter trawl

Until a few months ago, I had little appreciation for the intricacies involved in the build of an otter trawl, where many specifics combine to affect the 'selectivity' of the net, i.e. the relative proportion in which different fish species will be caught by the net (due to their differing behaviour that affects their escape or capture rate).

Factors such as the trawling speed, the size of the mesh and the shape of the mouth of the net while it is being towed through the water, are subtle factors that can drastically alter the selectivity of the net. Obviously we want to confidently replicate the fishing methodology, in order to ascribe any differences we might find between the catches of a century ago and those from our re-survey to changes in the fish community (as opposed to differences in the gear used). As such, we are paying close attention to these details and are gathering input and collaboration from a wide range of experts from the fishing industry, research institutes, net manufacturers and technical advisors.

We have now pieced together a comprehensive picture of the "large otter trawl" used during the Pieter Faure surveys. The findings of this research will be detailed in one of my thesis chapters and used to construct the historical trawl for our surveys in 2014/2015.

|

Historical ecology and SeaKeys

If anyone is interested in this project, or in the broader field of historical marine ecology, I encourage them to contact me. Over the next three years, I shall be coordinating a 'historical working group' under the auspices of a new national marine biodiversity project called SeaKeys: Unlocking foundational marine biodiversity knowledge.

This working group is focused around data rescue, digitisation and analysis of historical marine biodiversity data and we welcome any involvement by persons interested in these topics. The SeaKeys project is led by Kerry Sink (SANBI) and is funded through the Foundational Biodiversity Information Programme.

Acknowledgements

The Marine Research Institute at UCT and SAEON kindly provided travel funding for my overseas visit. The Marine Conservation Institute, National Research Foundation, SAEON and the University of Cape Town are acknowledged for their support of the project and my bursary. Thanks are due to Georg Engelhard for hosting me at CEFAS and inviting me to the ICES WGHIST meeting, as well as Mandy Roberts for kindly helping me navigate the CEFAS library and tracking down missing references.