Renosterveld restoration - reason to hope

With all renosterveld types in the Cape lowlands falling short of their conservation targets, ecological restoration has a crucial part to play in the future of the conservation strategy of the Cape Floristic Region.

In this respect, ecological restoration is necessary to alleviate the dire conservation status of these Critically Endangered ecosystems through buffering, enlarging, enriching and linking fragments - making degraded areas adjacent to fragments, for instance abandoned agricultural fields, ideal areas to direct such restoration efforts.

This study focused on Peninsula Shale Renosterveld, which is one such Critically Endangered ecosystem with a conservation target short-fall, with remnants situated either side of the Cape Town city bowl (on Signal Hill and the lower northern and north-eastern slopes of Devil’s Peak). The field experiment, located in the game camp on the lower north-eastern slopes of Devil’s Peak, occurs in an area that was most likely ploughed over a century ago and is currently dominated by alien annual grasses.

The need to restore this vegetation type has long been recognised; however, how best to go about implementing restoration efforts that are both effective and affordable is not as clear. Contemporary theory and practice do not have all the answers as the body of research addressing renosterveld restoration is small, albeit thankfully growing, and seed-based efforts have achieved limited success to date.

Underlying these limitations is a collectively poor understanding of the ecological processes in pristine renosterveld owing to centuries of dramatic alteration in the form of large-herbivore extinctions, fire-regime manipulation, intensified agriculture and alien plant invasions.

|

What has it all been about?

In this somewhat murky context, the research project needed to test the very building blocks of community recovery in response to the ecosystem drivers in renosterveld. It set out to determine the effects of interventions, implemented to mimic ecological drivers, on several seed germination criteria, the idea being that the most effective interventions (i.e. those resulting in communities with desirable attributes) can be incorporated down the line into feasible restoration strategies for Peninsula Shale Renosterveld and, potentially, other closely associated lowland renosterveld types.

Implementing interventions

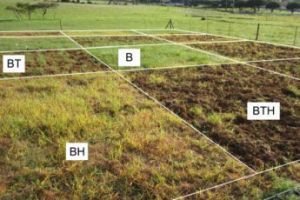

The five interventions selected and implemented were burning (to stimulate germination of the seed bank), tillage (loosening the soil to a depth of 150 mm to provide gaps and safe-sites for germination), herbicide-application (to reduce the effects of competition exerted by the alien annual grasses), rodent exclusion (to remove the effects of seed and seedling predation) and finally seeding (to act as a surrogate for natural seed dispersal and to test for dispersal limitation). These five factors were crossed to produce 32 intervention combinations (including the control) and these 32 interventions were subsequently replicated four times.

And the outcomes?

Seeding contributed significantly to overall seedling density, species richness and canopy cover. In a context such as this, seeding proved imperative in order to shift the community trajectory from one overwhelmed by alien grasses to one composed of desirable shrub and grass species. Recruitment in seeding-only plots confirmed that a lack of available seed (i.e. an inability of seed to reach the site) was a factor limiting community recovery, once again affirming the need to seed.

Yet, despite the positive effects of seeding, seeding only was relatively ineffectual and germination improved considerably when seeding was implemented in combination with one or more of the other factors, which functioned to reduce the alien annual grass element and increase the number of colonisation sites. In summary, the effects of rodent predation were negligible compared with the effects of seed-dispersal limitation and competition from the alien annual grasses.

In general, intervention effectiveness increased with the number of factors per intervention, yet, fortuitously, although interventions were costly, the most effective interventions were not necessarily the most costly. Some interventions resulted in good performances and have potential with respect to restoring self-perpetuating communities with a semblance of ecosystem composition, structure and function.

The interventions identified as potentially feasible and cost-effective were burning, tillage, herbicide-application, seeding (BTHS); tillage, herbicide-application, seeding (THS); burning, herbicide-application, seeding (BHS) and herbicide-application, seeding (HS).

|

Looking to the future

Monitoring of this project, spanning eight months (July 2012 to January 2013), has given close attention to the early stages of community recovery in response to the 31 interventions, yet, the value of extending the monitoring period for this restoration experiment is unquestionable. Tipping the scales from an undesirable alien, annual grass-dominated community to a more desirous shrubland community is central to realigning the community with a desired trajectory and to initiating effective restoration efforts.

For a more accurate and ultimately more useful measure of intervention effectiveness, longer-term monitoring is needed to determine a more meaningful reflection of intervention performance and to enhance our understanding of community recovery in Peninsula Shale Renosterveld and, potentially, other renosterveld types.

In closing, the findings of this study have shown that, despite the challenges, there is reason to hope when it comes to the future of restoration in renosterveld. The findings of this study have the potential to expand an already-growing knowledge base and seek to propel forthcoming research and implementation of ecological restoration of renosterveld into a future where the remnants of these valuable ecosystems are buffered, enlarged, enriched and linked to healthier prospects.

About the author

Penelope Waller is a SAEON MSc-candidate student, receiving a bursary from the SAEON Fynbos Node. She is studying towards her Masters in the Environmental and Geographical Sciences Department at the University of Cape Town under the supervision of Dr Pippin Anderson.

|