Delayed flights, deep sea and kimchi: My experience as an ISA trainee on board the R/V Kilo Moana

|

|

On March 5, I was at Cape Town International Airport in South Africa, waiting to board the flight that would kick-start my journey to the tropical islands of Hawaii.

I was practically dancing with excitement at the prospect of leaving my home country for the first time to rove international waters.

The opportunities that the training programme presented left me enthused and promised to be a memorable experience. While the idea of exploring a different country was truly enticing, it was the knowledge of the science that I was about to learn that left me feeling like I had been handed an all-access pass to the greatest show on earth.

|

My enthusiasm was put to the test when some of my flights were delayed or missed. Countless hours were spent in international airports filled with slight panicking, new friends and American food. If nothing else, I’ve come to know that the best lessons are learnt when things go wrong and that the Airtrain (found in some American airports) that transports you between terminals is only fun when you’re not lugging around heavy suitcases.

R/V Kilo Moana

The R/V Kilo Moana was docked at the Marine Biological Institute at the University of Hawaii where I met Isabel Garcia Arevalo, the second ISA trainee, Dr Kiseong Hyeong, the chief scientist and the rest of the team.

From the day of departure, it took six days to transit from Hawaii to the first of five sampling sites. Of course, the first thing we did during those transit days was watch the animated film Moana in honour of the ship’s namesake.

The remaining transit days saw Isabel and I trying to immerse ourselves in the Korean culture. I certainly felt privileged to learn more about and appreciate such a humble culture. I also learnt a few choice words in Korean, which almost certainly meant that we could be considered bilingual!

The Chief Scientist and his team were extremely accommodating and would readily impart their knowledge and wisdom. I enjoyed chatting to them over dinner about their research and was open to learning anything they could teach me.

Baseline surveys

Baseline surveys often form the foundation upon which seabed mining expeditions are designed. Mining essentially creates a disturbance in the surrounding environment as it displaces sediment and water. Knowing which organisms and processes are in place before this disturbance occurs will give an indication of its effects.

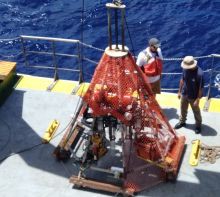

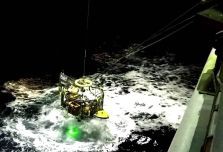

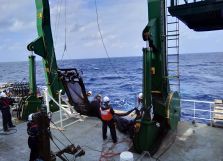

A variety of specialised instruments were used to conduct the surveys while ensuring minimal disruption within the target sample site and surrounding areas. A box corer and multiple corer were used to sample sediments of the seafloor. The Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System (MOCNESS) and zooplankton nets were used to sample the surface layers to a depth of approximately 2 000 metres. A deep-sea towed camera, operated by a team from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, gave us an indication of the seafloor topography, the density of polymetallic nodules and the type of organisms that are found on or close to the seafloor.

These and several other instruments gave us a good idea of the effects of seabed mining on the biodiversity and shape of the seabed and the nutrients in the water column and on the seafloor. For three weeks, the ship hummed with activity as scientific instruments were deployed and recovered, experiments were conducted and new discoveries were made.

|

Ramen noodles and kimchi

During our downtime, we watched the flying fish, whales and pods of dolphins that swam alongside the ship. At night, we were mesmerised by the squid that would migrate to the surface waters to feed. What was even more fascinating was watching the squid try to evade the sharks that could also be seen off the stern of the ship.

On quiet nights when no animals could be seen, we were in the lounge with our fellow scientists watching Korean dramas or playing the Korean version of poker and losing horribly. Failing this, the one place that we could always be found was in the galley.

As a courtesy to the Korean scientists, there was an abundant supply of ramen noodles and kimchi. Kimchi, a dish comprising fermented vegetables with chillies and red pepper, was a staple side dish served with every meal on board the ship.

Ramen noodles and kimchi had eventually become somewhat of a tradition for us, something we always found ourselves bonding over at midnight or at 3 am while waiting for sampling instruments to be recovered. It was at times like these that I would have to remind myself that the whole experience was real.

|

All in the name of science

There’s nothing quite like flying across the world to board a ship that would sail across the ocean. It takes a special kind of person with an adventurous spirit to feel at home when they’re isolated on a ship in open waters without the hustle and bustle of the familiar city life.

Scientists generally embark on journeys of this nature to make new and exciting discoveries “all in the name of science”. My mentor at SAEON, Dr Lara Atkinson, always told me “…you never know until you apply”. Months later, having had an experience that could not be justified in simple words, it all still seems very surreal.

I am grateful to Dr Lara Atkinson and Prof. Juliet Hermes for granting me the opportunity to be a part of something that was truly amazing.