Richard on top of his mountain

|

|

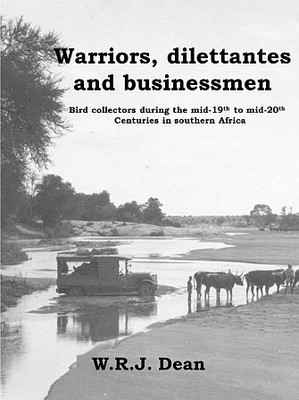

The dean of South African ornithology, Dr W. Richard J. Dean, reached further heights by revealing the depths of his knowledge in his book: “Warriors, dilettantes and businessmen - bird collectors during the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries in southern Africa”, published in March 2017 by the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Jacana Press.

The book is dedicated “To Sue [Milton], my colleagues and contemporary ornithologists. We reached the top of our mountain”.

We know Richard Dean, a SAEON Research Associate, to have immense experience and to be very thorough with everything he undertakes. This book is an excellent example, as it is something like the background of the background of ornithology, natural history museum collections, long-term records, and citizen science in South Africa, let alone a sprinkling of Richard’s own background infused between the lines, recognisable by those who know him.

This book is only the latest addition to over 200 previous publications by him, which include at least five previous books.

Tour-de-force

Warriors, dilettantes and businessmen is a tour-de-force through that period of history, 1850-1950, which brought natural history institutions, projects and scientists in southern Africa to the threshold of the modern age. Before 1850, collections and records were still scattered and localities often not precise; after 1950, collecting became institutionalised, moving into the realm of museums, and time was ripe for ecology and environmental sciences to develop on the foundation of these previous records and knowledge.

As historian, Richard illustrates the accounts of the collectors and collections as part of the fabric of history to be valued as enrichment of our understanding. Early colonial explorers kept detailed records and collected specimens. Later, the demand for natural history specimens for public and illustrious private collections opened the path for numerous professional collectors, whose trade became finding new species, remarkable specimens or special sets or suites of specimens. Increasing militarisation brought in soldiers with guns, time and the means to follow their interest in observing, recording and collecting specimens to meet the growing demand.

Museums gradually developed across southern Africa in the wake of the growing collections, eventually incorporating many private collections of birds and eggs and their records. Furthermore, many southern African collections were kept in museums in Europe and the USA. The accumulated experience and knowledge laid the foundation for ornithology as a mainstay of ecology, animal behaviour and biodiversity research, as well as the mainstay of citizen science in South Africa today.

Richard casts a slight shadow across the trail left behind by citizen scientists - amateur collectors who were either inexperienced or had vested interests for misreporting rarities - and the unknown levels of discrepancy between the advantages of numerous data collectors and problems with verification of historic data. Fortunately, this shadow appears to be quite light due to the contexts and nature of many consistent collections and records, reasonably safe for interpretation by cautious minds, as Richard points out.

Bird’s eye view

As scientist, Richard takes the reader a step back to look at collections from a bird’s eye view, from where we can continue to learn. The records document the decrease or increase of some bird populations and changes in distribution ranges. The accounts also document environmental changes of the habitats birds lived in.

Richard makes a strong case for museums as keepers of environmental archives. New data are constantly being derived from old collections using new techniques, such as DNA analyses, conservation genetics, and taxonomic revisions.

Likewise, new insights derived from old records can be critical for understanding modern environments. His plea for South African institutions to ensure curation of past data in order to enable understanding of today’s status and to predict future changes speaks volumes.

Although Richard’s book is only one volume, it packs a fair amount of human history, natural history, and personal professional history of the author into only 12 chapters in 196 pages, well worth reading.