Is the well running dry? A century of rainfall and streamflow patterns in South Africa’s largest protected area

|

By Dr Dave Thompson, SAEON Ndlovu Node and Ashley Lipsett, University of the Witwatersrand

Global climate change is not only associated with increasing temperatures, but also more frequent and prolonged periods of extreme climatic events such as flooding and drought.

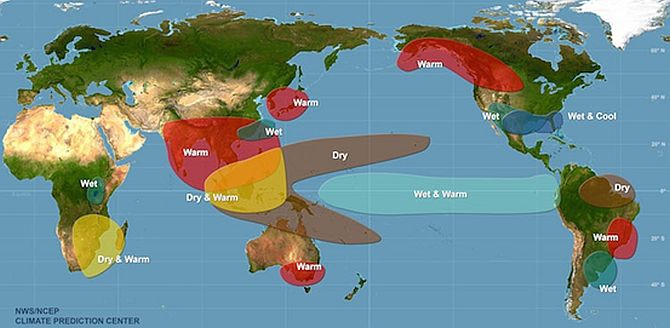

Climate change aside, such extremes are already commonplace in southern and South Africa, where ecological systems - particularly savannas, endure not only the annual seasonality of dry winters and wet summers, but also the periodic drier-than-normal conditions associated with the El Niño Southern Oscillation. This temporary reorganisation of atmospheric conditions disrupts global weather patterns (Fig. 1) and affects natural and modified ecosystems and the services they provide.

El Niño events historically occurred every three to five years, although recent scientific evidence suggests increasing frequency. For example, of the 27 events occurring between 1899 and 2003, 11 occurred in the most recent three decades.

|

Climate change and the continued disruption of weather patterns therefore pose significant threats to, especially, the already water-stressed semi-arid and arid regions of the planet.

Southern Africa is considered one of the most susceptible regions to climate change impacts as projected further increases in temperature and evaporation, documented increases in the number of warm periods, altered rainfall regimes, and modelled increases in the frequency and severity of extreme climatic events interact to negatively influence hydrological cycling and ecosystem integrity.

Without rivers, the freshwater lifelines of arid and semi-arid regions, much local biodiversity would not exist. Consequently the protection of rivers and their associated ecosystems is a research and management priority. Faced with the ominous, multiple threats of climate change it is crucial that we better -

- understand how river systems are changing;

- plan for these changes; and

- accommodate predicted change scenarios into river and protected area management policies.

Kruger National Park

South Africa’s largest conservation area, the Kruger National Park (KNP), protects a variety of flora and fauna, as well a range of diverse habitats. The high levels of biodiversity in KNP are supported by the park’s varied geology, temperature and rainfall seasonality and latitudinal gradients, fire, and permanent and short-lived water sources.

All but one of the perennial river systems in the park have their headwaters some 100 km or more outside of the park boundary. Research and monitoring have shown that water quality and quantity here are highly reduced by anthropogenic activities such as industry, agriculture and mining.

A 2013 pilot study carried out by WITS Honours student Ashley Lipsett revealed that KNP is directly affected by El Niño and experiences periods of drought lasting approximately 18 months every two to seven years. In contrast, non-drought periods have been typified, especially in more recent years, by devastating floods.

In her thesis Ashley highlighted a direct correlation between the El Niño cycle and ‘low flow’ of a subset of KNP rivers. However, scant additional work exists on the behaviour of KNP rivers as influenced by global climate change. One study (see Odiyo et al., 2007) links modelled river flow in the northernmost Luvuvhu River with rainfall variability, and another (see Kleynhans, 1996) highlights a trend towards annual, rather than perennial, flow dynamics for the same river.

A near 100-year window

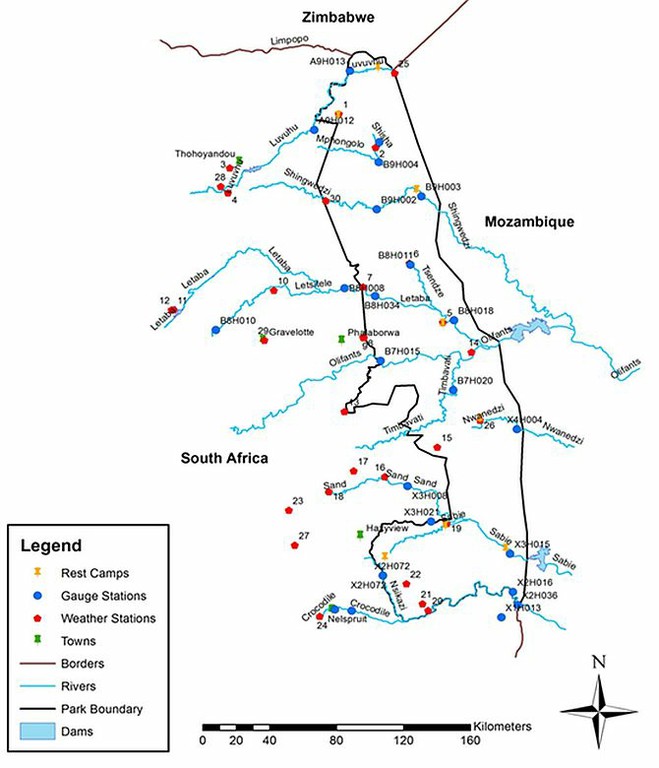

To address this shortfall, Ashley - now an MSc student from the School of Geography, Archeology and Environmental Studies (University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg) - is currently conducting trend-analyses of daily rainfall and streamflow data records for much of the South African lowveld (Fig. 2). These records date back as far as 1920 in some instances, providing a near 100-year window through which to investigate hydrological responses in relation to a changing climate. The records were obtained from the South African Weather Service and the South African Department of Water and Sanitation respectively.

|

Rainfall records cover 30 weather stations located in river catchments partly, and rarely wholly, within KNP, with 22 river gauging stations sited within or immediately west of the protected area providing corresponding flow data (Fig 3).

|

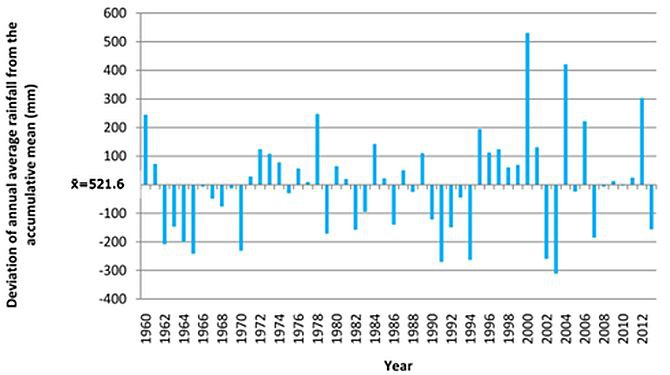

Under direction from Prof. Stefan Grab (WITS) and Dr Dave Thompson (SAEON Ndlovu Node), and with support from SANParks colleagues, the research being carried out aims to establish and compare rainfall and streamflow patterns over time for the eight main river catchments of KNP, and to correlate changes in inter-annual rainfall and streamflow. Initial time-series analyses suggest a breakdown in the predictability of the El Niño cycle from the end of the 20th century, and that climate extreme flood and drought events are becoming more severe (Fig. 4).

|

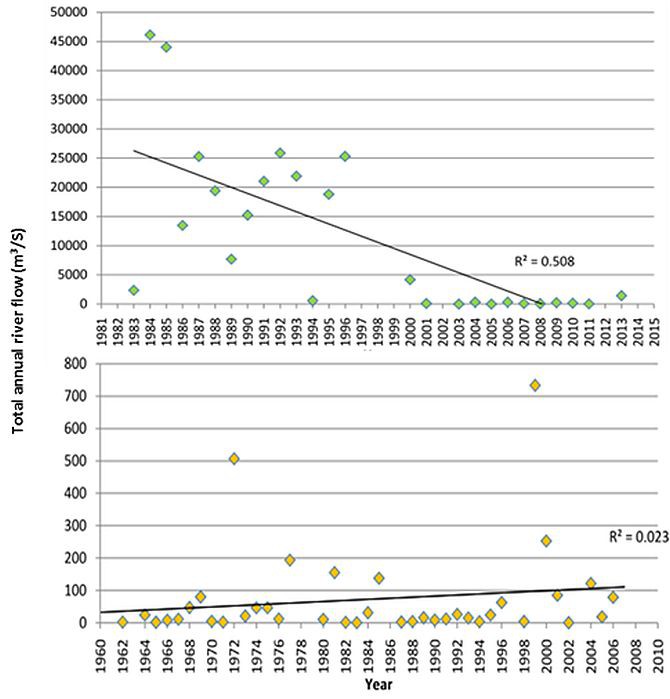

Typically, streamflow volumes have decreased substantially over time - particularly for the larger perennial rivers (Fig. 5), which in some cases have adopted an annual flow dynamic in recent years.

|

The ongoing research will further determine the effects and scale of impact of specific climatic phases, such as El Niño drought and tropical storm flooding, on streamflow. Because the river systems under study span the prevailing north-south rainfall gradient of north-eastern South Africa, all patterns and river behaviours are being interpreted within this spatial framework.

Determining the influence of climate on river dynamics

Comparing river systems that originate either within or beyond direct human influences, as enforced by the protected area boundary, will allow for a better understanding of how climate, in the absence of human land-use activities, influences river dynamics. Finally, and based on available rainfall projections, the researchers plan to model the likely future scenarios of rainfall and streamflow in KNP under plausible future climates.

Major concern has been expressed over the water quality and quantity of the perennial river systems of KNP, with the systems being significantly impacted by multiple land-use types before the water even reaches the western boundary of the conservation area. In line with the 1998 Water Act, park management currently focuses on water management at the catchment level to promote a balance between water use to sustain basic human needs and the sustainability of the water resource itself.

Crucial to this is the fundamental understanding that will emerge from this study regarding the interplay between river behaviour and a changing climate, and the relative impacts of climate and land-use on river flow.

References

- Odiyo, J.O., Phangisa, J.I. and Makungo, R., 2012: Rainfall runoff modelling for estimating Latonyanda Streamflow contributions to Luvuvhu River downstream of Albasini Dam, Physics and Chemistry of Earth Parts A/B/C, 50-52, 5-13.

- Kleynhans, C.J., 1996: A qualitative procedure for the assessment of the habitat integrity status of the Luvuvhu river (Limpopo system, South Africa), Journal of Aquatic Ecosystem Health, 5, 41-54.